For more than forty years, William S. E. Coleman has been researching and lecturing on the life and career of William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody. He has been recognized as one of the world’s leading experts on the theatrical history and staging of the Wild West, and has provided research, lectures, and presentations to museums, universities, and scholarly organizations throughout the United States, England, Scotland, Germany, Italy, and Sweden. Professor Coleman has one of the largest private collections of scholarly memorabilia in the world.

Preface

From the Author

In addition to my widely presented two-hour mixed media lecture, I have published several articles about the performance career of William F. Cody, the legendary Buffalo Bill. One was syndicated by the Iowa Press Association and published in more than 20 Iowa newspapers. As with most feature articles, it was not annotated; but its sources was drawn from Omaha and Des Moines newspapers of the time as well as other contemporary sources. The article below is substantially the same as that which was published, but I have added more information that I found after publishing this article. The illustrations, which did not appear with the article, are from drawn Buffalo Bill memorabilia my wife and I collected over the years.

Prairie Exhibition

Buffalo Bill's Wild West:

The First Performance

By William S.E. Coleman

Professor emeritus, Drake University

...and here he came, the leader of them all, dressed in his buckskin suit, the handsomest fellow alive, spurring swiftly up to the grandstand, and all of us jumping to our feet, cheering again and again. And then Buffalo Bill spoke, "Ladies and gentlemen, Buffalo Bill's Wild West, I salute you!"

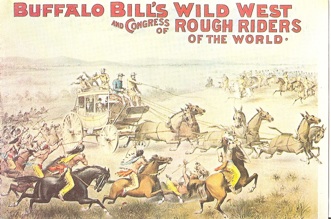

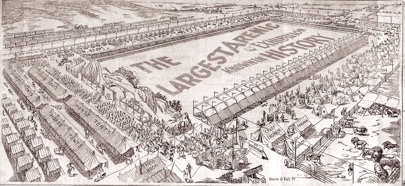

Then began a performance of one of the most popular exhibitions in the history of show business, Buffalo Bill's Wild West. The image we now have of the Old West was shaped by Cody's thirty-four consecutive seasons of touring. During those touring years more than 50,000,000 viewers between our West Coast and the Balkans saw Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in indoor and outdoor arenas. At least 100,000,000 more saw the street parades that preceded the more than 10,000 performances of the Wild West.

If these figures seem inflated, consider the fact that during 1886 season in the New York area, Cody's troupe played to nearly four million. A year later in London, they performed for two million more at Earl’s Court; and in one summer season during the 1893 Columbia Exhibition in Chicago, they played to six million viewers during two performances a day over 186 consecutive days in what was then the most successful run in the history of show business.

What these millions saw seemed to be an accurate picture of the American West, and to a large extent it was. Even Mark Twain felt compelled to write, "This show is genuine, wholly free from sham and insincerity."

The Wild West during its peak years was quite spectacular. More than 500 were in the saddle during a performance that included typical rodeo-like events featuring the horsemanship and marksmanship of Cody and his stars - Johnny Baker. Buck Taylor, Lillian Smith, and Annie Oakley.

Annie Oakley and Johnny Baker

There were typical frontier events such as an Indian or road agent attack on the Deadwood stagecoach, or an Indian attack on a settler's cabin. There were always with last minute rescues by Buffalo Bill. Actual historical events were staged, some shortly after the event happened, some of its original participants. Cody played himself in the 1869 Battle of Summit Springs and the 1876 encounter with a Cheyenne sub-chief, some called Yellow Hand.

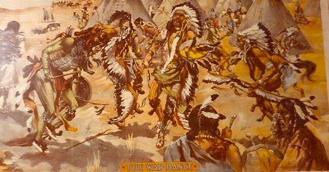

The Indians in the company had their day, too. They performed in a vivid dramatization of Custer's Last Stand. Chief Gall, who led the attack on Custer’s left flank in 1876, led the final charge.

Killing of Custer

This recreation was first staged in 1886 at Madison Square Garden in New York as part of a spectacle grandly called "A History of American Civilization." The entire production was more than grand. It was a lavish spectacle. Moving scenic drops measuring 150 feet long and 40 feet high allowed for rapid scene changes as a panoramic history of the West unfolded in an arena 400 feet deep by 200 feet wide. There was a recreation of a prairie fire and a stampede - and a mountain cyclone which blew cowboys from their horses - all this in the era of gaslights.

Madison Square Garden Scene

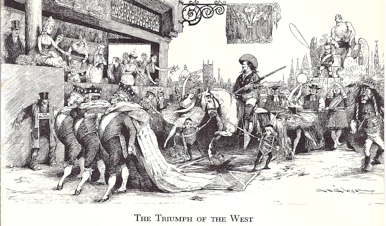

The spectacle was revived in 1887 in Manchester, England, and in 1891 in Glasgow, Scotland, but with one added feature - the landing of the Mayflower at Plymouth Rock. In other seasons there were more spectacles - a 1908 mountain avalanche indoors in Madison Square Garden, a train robbery with a real train, and the Battle of San Juan Hill shortly after it happened.

Crowned Heads at the Wild West

The Wild West spent nine seasons in Europe. Kings and queens, princes and princesses, politicians and members of the aristocracy rode in the Deadwood stagecoach during an Indian attack. Queen Victoria requested not one, but two, command performances. In 1889 the entire company received the blessing of Pope Leo XIII in Rome. The European craze for Western Americana and Western films, which still exists, can be traced to the tours of The Wild West. An entire generation between 1883 and 1916 underwent a Buffalo Bill craze.

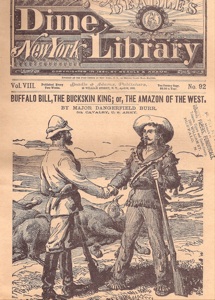

The craze began when Buffalo Bill appeared as a dime novel hero in Ned Buntline’s “Buffalo Bill, King of the Border Men” ion December 23, 1869 in The New York Weekly. The real Buffalo Bill, a minor frontier figure, was on his way to becoming a legend.

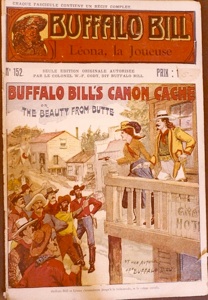

Dime Novel Covers

Buntline only wrote four dime novels that featured Cody as the hero, but there were more dime novels, many more. During Cody’s lifetime he appeared in 500 more, 1,700 if you count those in other languages and reprints.

National headlines confirmed that there really was a Buffalo Bill when Cody served as a hunting guide for the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia. Cody, Sheridan and General George Armstrong Custer met the Duke at North Platte, Nebraska, in January 1872.

Custer, Grand Duke Alexis, and Cody

The occasion also marked Cody’s first venture into showmanship. Prior to the hunt, Cody went deep into Indian Territory and persuaded Chief Spotted Tail to bring 100 warriors to the bivouac at North Platte. Once there, they simulated an attack on a stagecoach carrying the Grand Duke and performed a war dance in the evening. All this was covered in the eastern press. Cody took another step toward becoming an American mythical figure.

Within a month Buntline’s first serial was adapted to the stage by Fred G. Maeder and played at the Bowery Theatre in New York. Shortly after the opening Cody was invited to visit New York by George Gordon Bennett, the editor of the New York Herald. During his visit, Cody attended a performance of Maeder’s play with Buntline. When the audience realized that the real Buffalo Bill was sitting in the stage box, they insisted that he take a bow. The moment Cody stepped on the stage was a rare moment – a real man and a myth become one and the same.

Cody claims that the manager of the Bowery offered him $500 to play Buffalo Bill. Cody, though tempted, returned to North Platte where he continued to serve as a hunting guide for eastern celebrities and as an Army scout. On April 26, 1872, Cody was awarded a Congressional Medal of Honor for action at the South Fork of the Loup River.

A severe winter followed. Cody’s family had grown. Now he had a son and two daughters. Buntline had been writing Cody to encourage him to take to the stage. Cody in need of money took a train to Chicago with Texas Jack Omohundro. Buntline met them at the station on December 12, 1872. Ned was upset that they had not brought along Indians to serve as extras. Bill and Jack were even more upset to learn that Buntline had not yet written the play – and that the opening was four days away.

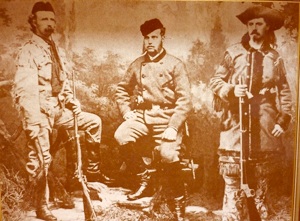

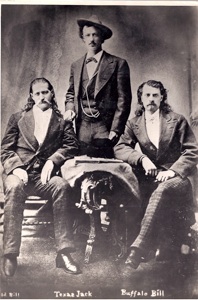

Scouts and Buntline

Buntline sat down, and with the aid of several clerks, wrote The Scouts of the Prairie; or, Red Deviltry As It Is in four hours. They opened on time with Buntline playing a trapper named Cale Durg and Cody and Omohundro playing them. Cody forgot his lines and improvised tales of his hunting adventures. The opening night was an artistic fiasco, but that didn’t matter to the audience. They were convinced they were seeing the real thing.

After a week’s run the play went on tour. Cody and Omohundro broke with Buntline at the end of the season and added Wild Bill Hickok as a co-star for part of the 1873-4 season.

At the end of the next season Bill and Jack parted ways. Cody continued tour as an actor until the end of the 1882-3 season in a number of plays that he commissioned.

While Cody was home in North Platte during the summer of 1882,

It was here that Cody developed the idea of an outdoor exhibition when he organized "The Old Glory Blow-Out," as part of a North Platte Fourth of July celebration.

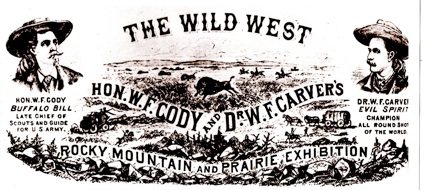

This inspired Cody to form a partnership with a dentist-sharpshooter, Dr. W. F. Carver. Together they sold shares and assembled a company for their touring outdoor exhibition.

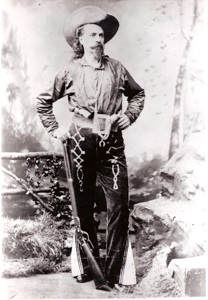

1. Wild Bill Hickok, Texas Jack, Buffalo Bill 2. “Buffalo Bill” Cody 3. Dr. W.F. Carver

Another participant, Major Frank North, who had headed a battalion of Pawnee Army scouts, recruited sixty Indians from the Omaha, Pawnee and Oglala and Brule Lakota tribes. Entire families, including babies and small children, joined the troupe. The pay was good - more than an Indian family could make on a reservation. For a summer, at least, they could live in tipis again and lead a migratory life, even though the migration was by train.

Indians In the Wild West

Most of the company’s eighty cowboys were Cody's North Platte neighbors. Many had played a part in the "Old Glory Blow-Out."

Buffalo Bill and Carver rehearsed during the first two weeks in May at Columbus, Nebraska. It was a convenient location near a Union Pacific railway station and several Indian reservations. After a hard day’s rehearsals, the company recessed to "Jack's" and "Charley's," two local bars. Most frontiersmen in those days were hard drinkers, and Cody was one of the hardest.

The final rehearsal was a fiasco. When Major North led an Indian attack on the Deadwood stagecoach, the six mules pulling the coach panicked. There was a runaway. Inside the coach were the mayor, Pap Clothier and his town council. Clothier had a short fuse, and when the careening stagecoach finally stopped he tried to attack Cody. Buffalo Bill protested, saying he wanted the attack to be realistic. Clothier, restrained by friends, screamed: "Realistic, hell! Let me get hold of you, and I'll make it realistic!"

DEADWOOD STAGE

North said the feature should be dropped. Cody disagreed. It was a good thing he did. The attack would be a stellar attraction in years to come. In 1887, at a performance at Earl's Court in London, Cody drove while Prince Edward, later to be King of England, and the Kings of Denmark, Greece, Belgium, and Saxony rode as passengers. In the royal box Queen Victoria and eleven princes and princesses watched.

The quick-witted Cody quipped, "I've held four kings, but 4 kings and the Prince of Wales makes a royal flush, such as no man ever held before."

After that, an invitation to ride in the Deadwood Stagecoach became the ultimate status symbol. To politicians of the era it was as important as kissing babies.

1. Deadwood Stage 2. Deadwood Stage With Dignitaries On Board

An excited Omaha eagerly awaited the arrival of the Wild West was eagerly awaited. The Daily Bee reported, "For a month past the great event to which our citizens looked forward was the appearance of the Cody and Carver combination, with their original Nebraska show." The Republican noted that it "was the principal topic of conversation, and groups...on the streets in animated discussion remind one more of a presidential election than anything else."

According to The Herald, local pride was involved since the Wild West was "a home institution, conceived by home energy and enterprise, and backed pluckily by home capital. Everybody wanted to see it 'go'."

The Wild West, now grandly titled "The Wild West, Honorable W.F. Cody and Dr. W. F. Carver's Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition," arrived in Omaha on a special train of ten cars at the Union Pacific shops 4 o'clock in the afternoon, Wednesday, May 16.

1. Unloading the Train 2. Street Parade

The company disembarked and marched up 16th Street to the Driving Park. The procession, which included cowboys, Indians and their families, rolling stock, horses, buffalo and six elk was, to quote The Bee, was “very novel and well calculated to attract attention."

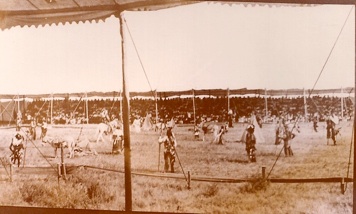

The troupe set up camp and began to prepare for a 2 pm performance on Thursday, May 19, 1883, at the Driving Park in Omaha, Nebraska and a scheduled three-day run. Then storms ripped through the Omaha area, blowing down houses and barns in South Omaha. The Wild West cooled its heels for two days. So did the 3,000 visitors who came to the city on special trains to see the exhibition.

Cody, always the showman, had the Deadwood Stagecoach dash through 15th Street and into Farnum, stopping at the Paxton House. A crowd gathered to examine the historic vehicle as its riders left it unattended while they entered the hotel bar.

There was a street parade on Saturday morning, May 21. The crowd that watched it followed it to the Driving Park.

There they could visit the encampment and the Indian village.

Indian Village

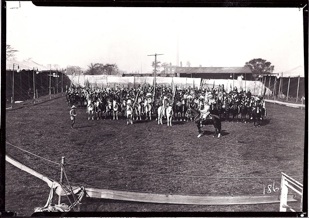

The stands were filled with between eight and ten thousand viewers

for the two o'clock performance. There were ten events in the program.

First, there was "a grand introductory review of the Wild West."

Wild West Program -1883

Wild West Band

A twenty-piece band, led by Cody's North Platte neighbor, William Sweeney, played as the entire company rode by the grandstands before a wildly cheering crowd.

There was an Indian pony race with a dozen riders, an illustration of the changing of horses by Pony Express riders, the Deadwood stage attack, a 30-yard race between an Indian on foot and a cowboy on horseback (with the Indian winning), shooting exhibitions by Captain Adam Bogardus - the champion pigeon shot in America - and by Carter and Cody, cowboy's fun which included bronco busting and lassoing, a buffalo and steer chase, the Indians on the warpath and "a grand closing equestrian act" which led the company into what the program called a "furious finale.” The first Wild West was raw and rough hewn, a loose combination of rodeo and frontier events. However, there was one reenactment – the “Royal Hunt” Cody staged for the Grand Duke Alexis. Other reenactments would follow in the years to come, some recent, some in the past.

Indian Camp War Dance

In the evening the Indian camp again was opened to visitors. There The Republican reports, "A glance into the tepees revealed a scene of comfort, if not luxury. In the center of each a bright fire glowed and the curling, blue smoke sought its way upward through the opening of the tent." Outside the Indian men staged a scalp dance which "held the spectator entrances...as the warriors...decked in the most gorgeous finery...danced a wild, weird dance.

That same evening Sitting Bull arrived from the Rosebud Agency. The Bee complained, "This breaks the charm of the show as a strictly Nebraskan institution. Mr. Bull's stomping ground is in Dakota and Montana.” [NOTE: I question whether this was the famous Lakota Sitting Bull. This performer was labeled elsewhere as “Sitting Bull of the Arapahoes.” Indeed, if he was the great Lakota medicine man, he did not travel East with Cody.]

Buffalo Bill and Sitting Bull

INDIANS WITH WILD WEST

Some writers claim that Cody exploited the Indians in his exhibition. Their contracts were reviewed and approved by the Department of Interior. The Indians in the exhibition were paid as well as some of the white performers. Indeed, stars like Sitting Bull were paid as much as the white headliners. Other Lakotas competed to tour with The Wild West.

In Sitting Bull’s only other tour with The Wild West during the summer of 1885, his contract dictated that he was paid $50 a week. An advance on his salary was banked. He also received bonuses and retained all photographic rights. Salaries were paid to his two wives and a daughter, a translator, and five warriors in his entourage. No agent could have driven a harder bargain. In 1885 that was big money. Two of Cody’s headliners, Johnny Baker and Annie Oakley, earned less. In Canada Sitting Bull’s appearances were treated like those of a national head of state.

A second performance was added Sunday afternoon. The real hit of both afternoons, though, was the attack on the Deadwood stage. On Sunday The Bee reported the event was especially "thrilling and dramatic" and "the immense crowd went nearly wild over it," demanding that it be encored.

The Bee critic was correct in predicting "The Wild West was destined to make a big hit in the East, and the managers will reap a rich harvest from the investment they made upon such big chances."

Cody agreed with that assessment. The Omaha Herald reports that after the Sunday, May 20, 1883, performance Buffalo Bill held court in a local bar, asking, "Where is Barnum now with his greatest show on earth?" Then. After asking the adoring crowd up to share a drink "for the fifteenth time," Cody boasted, "I'll come back to Nebraska next fall with my celebrated Deadwood stage chock full of dollars. I tell you The Wild West is bound to take the East. It is a genuine Niagara of novelties all lariated from Nebraska and complete in every particular."

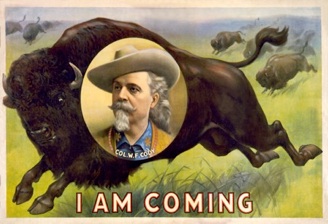

Promotional Poster

It was not an idle boast. In years to come The Wild West outdrew all other indoor and outdoor exhibitions here and abroad. Part of this success was due to the novelty of his spectacle. Part was due to the fact that it was neither a show nor a circus, two terms Cody despised and refused to apply to the Wild West. Instead, he saw his exhibition, as he called it, as serving an “educational purpose to present frontier life," to use a phrase from his programs.

Cody left the bar in time to catch a train to Des Moines, Iowa, at eleven that evening. After an all night journey, there was a nine o'clock parade through downtown Des Moines and performances at two at the Fairgrounds on Monday and Tuesday, May 21 and 22.

The Des Moines Leader reports, "There was an attendance of perhaps 2,000, who were, on the whole, pleased with the program offered." The Iowa State Register predicted "that as the Wild West gets farther East, where the Indians and plains life are more removed, the show will draw like a circus."

One critic worried, "Were it not for the free, breezy life of the plains - trapping, hunting, scouting, Indian fighting and all - is a thing of the past, the Register would doubt the effect of the Wild West exhibition on the inflammable imaginations of the young."

In years to come, as the Wild West wended its way into show business immortality, it stirred the imaginations of old and young alike. An entire generation vicariously lived the danger and adventure of the Old American West as Buffalo Bill Cody created his own myth and an enduring vision of an era that was disappearing. In time that vision found its way into western films. In them, and our own imagined memories, all of us share what Buffalo Bill created.

May 19, 1883, is indeed a day to remember.

Buffalo Bill