Amidst A Band Of Brothers

More than 10,000 men were crammed aboard the Aquitania. Bunk beds were three and four tiered. Some of our gear was tagged and stowed away. The rest was tucked beside the bunks. Most of us made our way to the main deck. There we watched tugs pull us out into the harbor. Shortly after that we sailed past the Statue of Liberty. Then we cruised into the wide ocean ahead of us. We were underway.

There were no convoys for the large troop ships. Instead, they took off at full speed after we passed the Statue of Liberty and zigzagged across the Atlantic in five days. They were too fast for lurking U-Boats. I was quickly seasick and almost as quickly hit with dysentery that I contracted from eating the greasy, badly prepared British cooks. My dysentery persisted throughout my five weeks of infantry combat. It and my weakened ankle were with me until the end of the war. Once I had good US Army food at the end of the war, my dysentery subsided. The sub-dislocated ankle is still with me.

We landed in Scotland, took a train south. There was no stopping, no chance to see London. When we arrived at Southampton, we got off the train and boarded an enormous ferryboat. That night we slipped across the Channel. Nazi bombers and fighters still threatened channel boats. We arrived in bomb torn Le Havre long before dawn.

THE REPO DEPOT

We disembarked carrying everything the Army had issued us. Our load was well over fifty pounds. The ankle that I sub-dislocated in basic training and which put me in a hospital for a month creaked and ached as I walked on the cobble-stoned path to a huge tent city, a Repo Depo called Camp Lucky Strike. All the Repo Depots were named after cigarette brands.

As we trudged up a cobble-stoned road, my weak ankle creaked and pain shot up my leg. My concern was whether my ankle would stand up in combat. In one way, I I felt that I would be relieved not to face enemy fire; but I felt more strongly that I was part of a group of many men. While I did not want to go into combat, I did not want to shirk my duty. At eighteen, that kind of thinking was a lot to deal with. My main fear was not of dying. It was that I would be maimed.

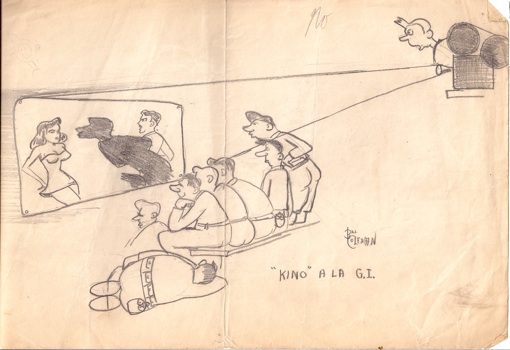

While we waited for a train to take us north toward Germany we had three or four evenings.

One evening was spent in Le Havre, another watching a film, Rhapsody in Blue, in tent theatre. The projectionist’s assistant regaled us with dirty jokes as reels were changed. Some were very good, some were merely disgusting. Rhapsody in Blue seemed to be one of two films available for overseas viewing. The other was Bowery to Broadway, a low budget musical starring a young Donald O’Connor and Peggy Ryan. I saw each film three or four times while I was in the ETO (European Theatre of Operations).

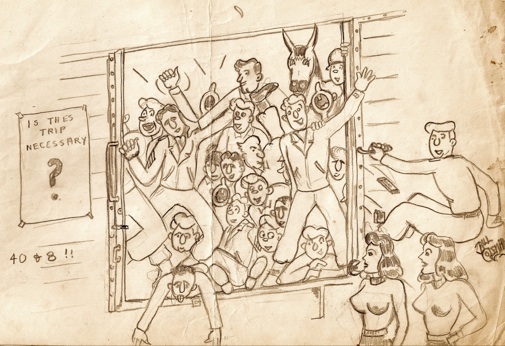

40 and 8

Bars of soap were snapped up for the equivalent of dollar, a pack of cigarettes for two dollars. If one had had the foresight to bring along a pair of nylon stockings, the French women would do almost anything in return for them. Later some GIs found that German women would do everything for any momentary luxury.

Money had little value to the French and German civilians. The mark had no value. The franc had minimal value. Our government printed money that we were supposed to use to buy things we needed. Often it was refused. Barter was preferred. To survive during a war, civilians mustered every commodity they had. Selling their women for sex was one of their prime commodities. As an innocent eighteen year old, I found this upsetting.

Town after town was in ruins. At times it seemed like a steamroller had plowed through France not too long ago. I am sure people were dying of starvation and disease.

After the war ended and while I served as a cartoonist at Battalion Headquarters, the owners of the printing business that published our battalion history gave me a book of paintings by a German war artist named Hans Lisova. [Since his name never appears in print, I am not sure if I have his last name. His signature is slurred.] His watercolors do not idealize the war. He seems to have observed ground and air combat first hand.

Lisova caught the ruins of war in several of his paintings, but he caught it from the point of view of a German whose armies created the ruins.

TOWARD THE FRONT LINES

On our arrival in Germany, we were assigned to the relatively young 76th Division, the Onaway Division. Onaway is Chippawa cry to be alert. It had gone on line near the end of the Battle of the Bulge and was part of Patton’s Third Army. Our patch reminded me of a telephone.

In retrospect, I was fortune to have been assigned to the Third Army. Patton’s fast moving troops suffered fewer casualties than other American armies that spread along a long front that reached from the Channel to Switzerland. We were never put in an extended confrontational situation. If we encountered heavy resistance, we circled it and cut it off from supplies as we moved ahead toward the center of Germany.

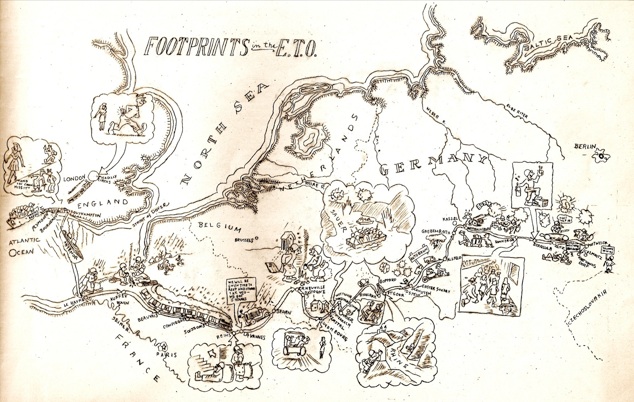

After the war ended and occupation duty began, I was assigned to be a cartoonist and writer for work on our First Battalion (417th Infantry Regiment) history.

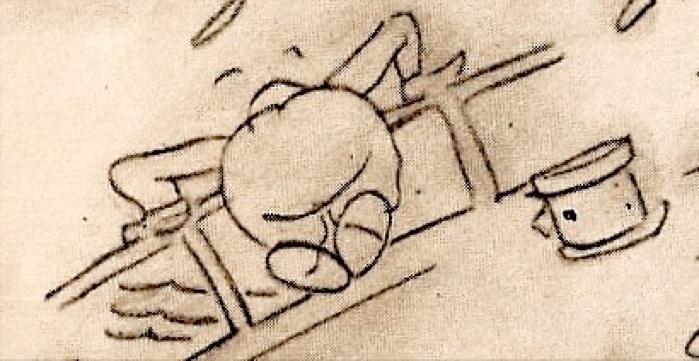

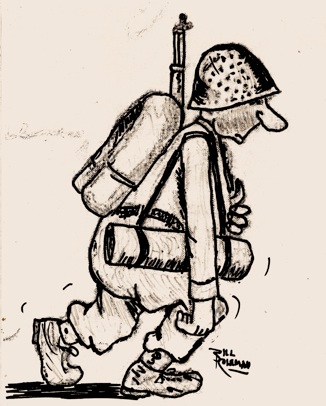

Four of us collaborated on this map of the 76th progress across Europe. I became adept at miniature illustrations. The cartoon of the seasick soldier and the entry into Le Havre are tiny inserts into the history’s text.

LIFE AS A HUMAN PACK HORSE

The BAR was the base of our firepower. I carried a belt filled with a dozen or so of its heavy twenty bullet cartridges. I had to stay close to Reed so he could have more cartridges if he ran out of his own. This was an older weapon, a limited hand-held machine gun, but it could spew out a torrent of bullets.

I carried a M-1 rifle which cartridges holding eight bullets, but one by one. It replaced the bolt-action Springfield rifles used in previous wars. It weighed 9.5 pounds. It had a nice balance. After a week on line, I quickly learned to “fast draw” and shoot from the hip. Usually we could fire off a clip of eight bullets simply by pulling the trigger eight times. There was no need to operate a bolt action.

My first M-1 jammed during my first firefight. As we charged the enemy I fired, pried out the bullet casing, fired again, and repeated that until we ended the firefight when the German soldiers were dead or surrendered.

My second M-1, nicknamed “Corky” by its former owner, was amazingly accurate. When I speak of a former owner, I mean he was a rifleman who was wounded or killed in action. He had lovingly carved its nickname on its stock.

The M-1 had one serious drawback. It jammed if its chamber and trigger mechanism wasn’t scrupulously clean. If you dove for cover, you could scoop dirt into its action. If so, you had one shot, a jam, and then you had to use a small tool to remove the expired clip. This was difficult to do when you were under fire.

BAR cartridges contained twenty rounds each. I carried at least twenty, or a total of more than 30 pounds. I carried also ammo for my M-1. Each of the cartridges held 8 bullets, and I carried at least thirty. I also attached as many grenades as I could to my uniform, a grenade launcher which could be attached to my M-1, a canteen and mess kit, an entrenching tool, a poncho, a bayonet, and two trench knives – one was on my ammo belt, the other was strapped inside my sleeve. I hid it there in case I was captured. If the Wehrmacht captured us, we knew we would be treated humanely. If the Waffen SS captured us, we knew would be treated badly. I wanted to be ready to fight to the death if they captured me.

I carried at least 3 K-rations and as many clean socks as I could tuck here and there. Inside my helmet I stuffed wads of toilet paper. I also carried a Bible my parents bought for me. It had a steel jacket, so I carried in my field jacket’s pocket over my heart. I also carried two pocketbooks – one of poetry, the other of classic short stories. I humped more than fifty pounds.

We only attached our bayonets when we received that dreaded order, “Fix bayonets!” The idea of bayonet fighting terrified me. While it requires some skill and ability, sheer strength and size is a strong asset. I had to fight with it twice. Obviously, I am lucky I came out those encounters alive.

I was still suffering from dysentery and the right ankle I sub-dislocated during Basic Training. It creaked and ground bone on bone. Intermittent shots of pain ran up my leg, especially when we charged the enemy. Others in the squad had dysentery and other ailments. To those of you who are young and think that being in combat is glamorous and exciting, please believe me when I say that being in the Infantry combat is not. Those television-recruiting advertisements are glossy lies. Infantry combat combines sheer endurance with sheer terror. I strongly advise you to never enlist. If there is a draft, move to a country that will shelter you.

You may have noted that the riflemen I drew all have stubbly beards. At eighteen I unable to muster a noticeable stubble. Patton sent orders down to all his troops that we should all be clean-shaven and wear our uniforms properly. There was a threat of a court-martial if we didn’t. No one paid any attention to these directives from far above us. We knew Patton – in spite of the legends that now surround him – would never visit us at frontline company level.

I will say one thing in defense of Patton. I believe I am alive because of him. He kept his units moving and never put them into a prolonged head-on battle. We moved quickly and usually outflanked the enemy and left him cut off without supplies. Usually our firefights were fast. Even so, I believe that his genius grew out of his madness.

AT THE FRONT

Steven Ambrose, the great military historian, wrote, “Infantry combat is the most extreme experience a human can endure.” Infantrymen in World War II were unprotected. Now they wear body armor that protects their torsos. Many who survive now are horribly maimed. Then they would have died from body wounds. Across generations we are all brothers. We are all statistics - cannon fodder and expendable. The section that follows doesn’t come to grips with the horrible reality every dogface faces. Perhaps that is just as well.

At first I ran day and night patrols that often went behind enemy lines. Eventually we ran patrols that took us to bluffs looking down and the Rhine River and the small towns on the other side. There we saw German troop movements as the Wehrmacht prepared for our crossing of that wide, historic river.

To be continued...