Into The Heart of the Third Reich

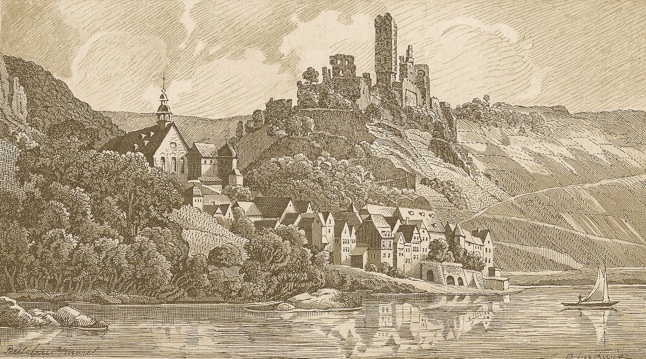

This old woodcut may seem to be an idealization of a Rhineland vista, but it was not unlike what we saw when our day patrols reached the bluffs above the river. We knew the peaceful view across that great river hid many dangers. As we waited to cross the Rhine, we wondered what lurked inside those quaint old buildings.

Sometimes patrols were assigned by lot; but when our Assistant Squad Leader Carlos Bustamante led a patrol and asked for volunteers, I volunteered. He took daring chances on his patrols and took us far behind enemy lines to places we were not expected. Like Patton, his daring made his patrols less dangerous than other patrol leaders. . In looking back I am amazed that I had no fear when I was on patrol. It didn’t matter if we were exposed by daylight or masked in darkness. I felt a calmness, a sense of purpose. Perhaps I was too young to know better.

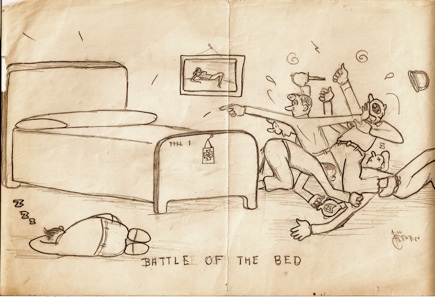

Sometimes, when we stopped for the night, we were billeted in German houses. Since there were not enough beds for a squad of twelve men, there was a spirited rush to claim a bed. Usually, three or four of us slept in one bed.

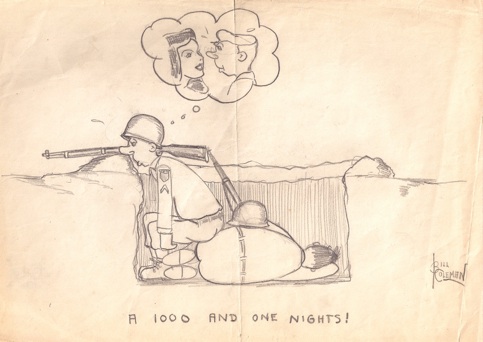

While I teamed as Assistant BAR man with an older soldier named Reed, I dug in with Larry Freeman. He was a tall, rangy guy, the son of a Georgia sharecropper. He was well read and highly intelligent. We remained friends after the war ended. In time our correspondence dwindled and faded away. I hope Larry has enjoyed a great life.

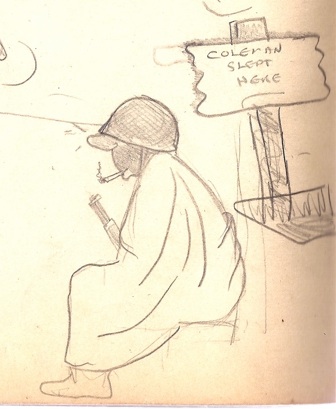

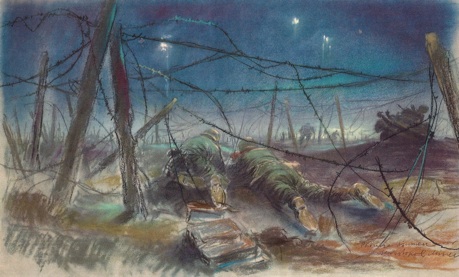

Many of our nights were spent in foxholes. We hastily dug in as darkness gathered. They protected us from shellfire. Only a direct hit could kill us. They also were deep enough that tank treads would ride over us.

FOXHOLES AT THE FRONT LINES

The recommended dimensions of a foxhole was six feet long, three feet wide, and four feet deep. They were not unlike a grave, but they were much shallower. Two men could dig one in an hour if the ground was soft. If the ground was hard we took the risk of not digging in even though we knew that if Panzers attacked, we would be dead.

One morning I awakened to find a corner blown out of a foxhole I shared with Larry Freeman. We had slept through a shelling. Those boyhood nights I spent sleeping next to the railroad tracks in Parnassus paid off. I still can sleep through loud storms. Since I have at least a week’s gap in my memory of my time in combat, I often wonder if I suffered a concussion when that shell missed going into our foxhole and killing us. Or could it be that I died that night and am now living in another dimension? Perhaps that explains the wonderful absurdity of the improbable life I led after the war?

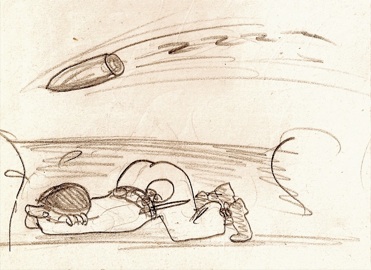

This is one of my non-cartoon sketches. A few are scattered through my sketchbooks. I wish I had done more.

A survivor of the Battle of the Bulge said, “In combat, dying is a lot easier than living.” That is very true. It is also true that one’s mindset is that death is something that happens to someone else.

There comes a time in combat when you are so tired that you no longer care about living. Only your body’s primal instincts keep you alive. That happens when a deep weariness permeates your body. More than once I did not care if I lived, but I still functioned as a soldier. I feared being maimed. My senses and my body seemed more important than dying.

After the war ended, I treated foxhole life humorously. Laughter softens harsh memories.

A foxhole could protect you from everything except a direct hit or a tree shell burst. We never dug in a wooded area. Tree branches could detonate a sheland send down a shower of shrapnel.

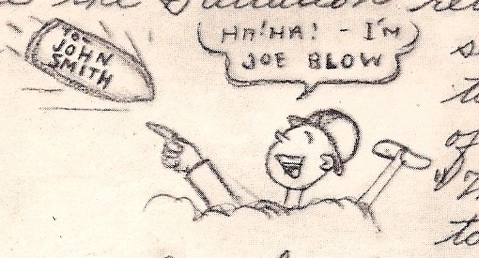

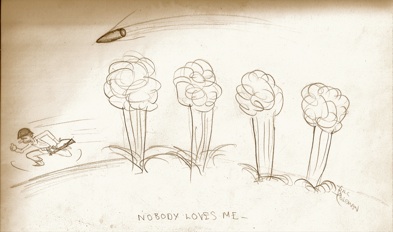

In war movies there were frequent references of that particular shell that had your name on it. I turned this into a joke.

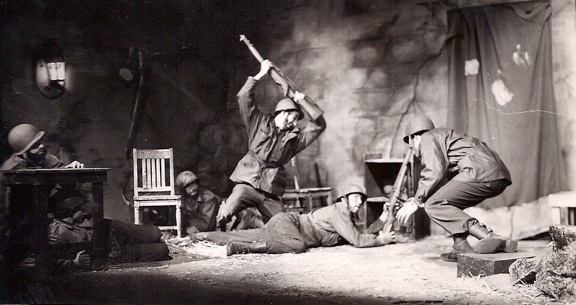

Sometimes we took refuge in a cellar. My play, Pillars in the Night, which was directed by my late playwriting professor, Warren Smith, was performed at Penn State the fall after I completed my MA. It was set in a cellar. I recently read it. It is a good play, but it requires 17 actors. That is too many for present day theatres. I will never forget Warren’s production of my play. He realized my play beyond my wildest dreams.

No play of mine has ever been better directed. The incredible thing is that Warren, a member of the Society of Friends, caught the tension and horror of Infantry combat with precision and vivid reality. The conversations I had with Warren regarding pacifism wera great influence on me.

The production was accurate in its costumes and equipment. The cast could not have been better. Kneeling at left is John Aniston; a now retired television star, and the father of Jennifer.

The play centered on a self-inflicted wound by an infantry squad’s Sergeant.

While nothing like that happened in our squad, self-inflicted wounds happened with some frequency in Infantry outfits. Such a foot wound was called a “million dollar wound” – a wound that got you home.

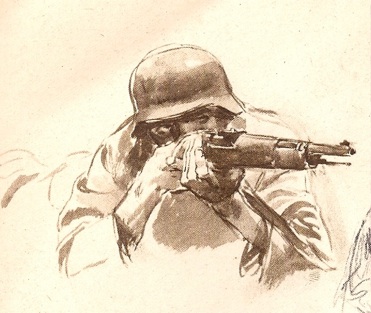

To the right and below is another of my non-cartoon drawings. It depicts a fully equipped rifleman.

BAZOOKAS

As an assistant BAR man, I was relieved not to have been assigned to a Bazooka team. One man aimed and shot it; another loaded and twisted a wire around a terminal. When the trigger was pulled an electric charge fired the shell.

A Bazooka team was our best weapon against a Panzer attack. With one well-aimed shot they could stop a Tiger tank. If they missed they had a real problem. A Bazooka when fired unleashed a flame out the back of its tube. Its shell was essentially a rocket. The Germans would see this blaze and bring fire down on the Bazooka team. An experienced Bazooka, after getting off a shot, threw away their Bazooka and ran to cover. In just one day our team went through three Bazookas. Snipers also tried to shoot a man carrying one of these weapons. Our officers chided our teams for this waste of a fine weapon, but no one was willing to risk their live to save a weapon that could be replaced. The BAR-man was equally vulnerable, but not as easy to identify from a distance.

American made tanks, while fast and agile, were poorly armored and vulnerable to a German 88 shell. They were weak offensively since their 105 shells could not pierce the heavily armored German tanks. I actually saw a shell bounce off a Tiger tank and explode on the ground behind it. Our auto industry did not do its job when it came to tanks. Even then the bottom line was more important that our lives.

Patton recognized this weakness. When the infantry faced a tank attack, he pulled back his armor and allowed the Bazooka teams to deal with the slow German tanks. He used his tanks speed to break through lines and speed ahead. When our tanks were on the offensive, they were effective. On the defense, they were relatively useless. I believe this is why the Third Army rarely held a position and waited to be attacked, as Montgomery did. Instead we moved ahead.

Most casualties happen when a unit is in a fixed position. There the Germans could shell us with their vicious 88 howitzers and rocket Screaming Meemies. In a way, our military industrial complex’s cheapness in armoring our tanks saved my life as an infantryman because with Patton were always moving forward. I can proudly say that in my five weeks of combat our squad never took one step backward. We were always on the attack even though we were foot weary and ill with dysentery.

Our industry’s desire to make profits from war is still evident. Our Humvees lacked armor of any sort. Our troops had to weld armor on them in the Iraq and Afghanistan war zones. Added to that, our men and women were forced to buy their own body armor. When it came to the bottom line there was no best for our boys.

We had no body armor. While armor has saved thousands of lives in Iraq and Afghanistan, it did not save arms and legs. That is the reason we see so many maimed soldiers on the news. As for me, I did not fear death as much as I feared being maimed.

A BADGE OF HONOR

After a week in combat Infantrymen with a rank up to Captain received the Combat Infantry Badge. Too many officers of higher rank wear it. It was designed to honor men who served on the front lines day after day, not a Major, Colonel, or General who visited the front for a day when there was little action. It is one of my most prized possessions.

With it came a ten dollar a month raise in pay. Of all the honors an infantryman can earn, this one meant the most. It meant that you survived battle for at least a week and served with other brave men. At the same time I was promoted to Private First Class. That meant five dollars more a month. Now I made sixty dollars a month.

In addition to my Combat Infantry Badge, I was awarded two Bronze Stars. I put this award out of my mind until Linda noticed the awards on my discharge papers a few years ago. I sent a copy of my discharge papers to the Army and received one of my medals. It sits on our mantle. I cannot explain why I walked away with my Military Discharge in hand and didn’t pick up my Bronze Star. I would like to think I rejected it because it had been cheapened by the officers at First Battalion Headquarters who wrote up medals for non-existent heroism at front lines they never visited. I think it was more likely I was in a hurry to get the hell out of Camp Atterbury and get on my way home.

The Bronze Star was the enlisted man’s medal for bravery. If one did something truly exceptional, he was awarded a Silver Star. If he did something even more exceptional he was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross. The Congressional Medal of Honor was reserved for those who were truly brave in action.

Rear echelon offices (those in Battalion Headquarters and further back) coveted these medals. Career officers needed medals for advancement. When I was assigned to First Battalion Headquarters as a writer/cartoonist, I frequently overheard officers conspiring to write each other up for medals for acts of courage that never happened.

Like the Combat Infantry Badge, the Bronze Star belonged to those who slogged it out in the front lines. I am sure all of you have seen generals with a chest full of medals. We nicknamed these “fruit salad.” Most of the ribbons stand for insignificant accomplishments. There was a ribbon for being in the United States during the war and another for being in the Army when the war ended. A high school chum of mine who was never overseas strutted about New Kensington on patriotic holidays with four rows of ribbons.

ON THE ATTACK

In combat you feel the entire war focused on killing you. You feel exposed, and there is nowhere to hide. Any second can be your last.

This cartoon reflects that feeling.

It is not a drawing of a real event. Instead, it is a variation of a reoccurring nightmare I had for several years after the war. I drew it out of my subconscious.

Sometimes my dream was in a pitched battle. Some dreams were in towns, some in fields and forests. The worst of my dreams came during street fighting. You never knew what was around the next corner or behind closed door. Sometimes I woke up screaming.

Hans Liska paints his impression of the German troops we faced. [When I wrote the previous section I did not know Liska’s name. Since then I researched him and found that he had been an official Wehrmacht artist in Greece, Russia, and other European countries.

He remained an artist for the rest of his life. My battered copy of his wartime paintings and drawings is autographed.]

Below is a Wehrmacht sniper drawn by Liska.

As we advanced snipers picked off men. Death came with no warning. Probably there was no pain. Suddenly you were dead. No one in our outfit killed by a sniper.

Snipers were used when an army was retreating. We had need for snipers. We always moved forward.

I take great pride in the fact that our company never retreated during my five weeks in combat.